by Susan Zimmerman-Orozco

Susan is an elementary ESL teacher in Montgomery County Public Schools and consultant with English Learner Portal.

I love co-teaching with the Lucy Calkins program. I get to use my expertise as the purveyor of academic language. At the same time I’m learning from my co-teacher, my mainstream students, and the Lucy Calkins writing guide.

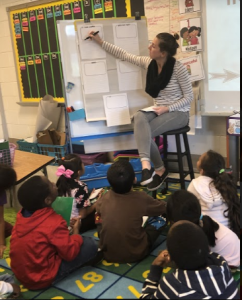

Once or twice a week I plan and teach a whole-class lessons that ESOL-izes concepts that I know are mystifying my English learners, or it anticipates confusion in upcoming lessons  by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom.

by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom.

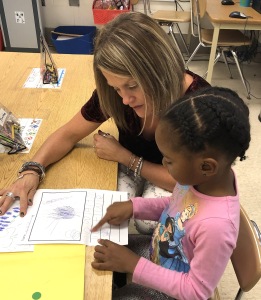

Arguably, however, the most valuable component of the Lucy Calkins approach to writing, and where I feel I make my most valuable contribution, comes from the frequent opportunities it provides for teacher-student conferencing. In the traditional Writing Process approach, dedicated teacher-student conferencing doesn’t appear until quite far along the continuum, after students have brainstormed, created drafts, peer edited, and revised their work. English learners, though, as we know, need quite a bit of hand-holding and scaffolding to be successful writers, especially if we want them to advance in their proficiency by adding more academic-level vocabulary and complexity to their writing.

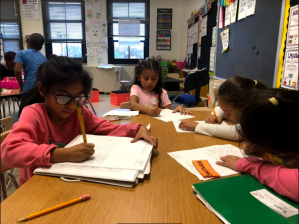

In our co-taught classrooms, daily, once a whole-class lesson is presented, students  return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.”

return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.”

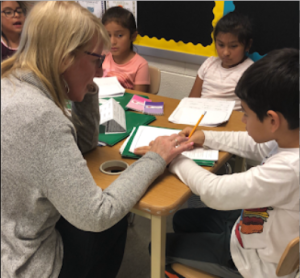

Our groups are fluid. Some students just prefer to work on their own, and we have some highly productive student partners who produce inspiring writing conferencing only with each other. I often work with non-English learners, and my amazing co-teacher, Tara, is  so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.

so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.

Furthermore, and frankly, as a school with a highly diverse population, some of our students come to us better prepared than others to work independently. As Tara commented, “Conferencing in a group limits unwanted behaviors that would distract others. In a group setting, sitting all together at the table, I can conference with one student, get him or her on the right track, and quickly move on.”

She continued, “I feel all of our students need support, and more than anything they need reassurance that they’re doing the right thing.” Referring to some of our students with behavior concerns, she added, “Sometimes kids who are the most reluctant writers act out because they don’t want to fail. If I’m there with them, insisting they can do it, and helping them, I can show them that writing doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and they CAN succeed.”

I know I’m not alone in feeling that the Lucy Calkins Writing program in particular, and  probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

One of the most satisfying and unexpected outcomes of working with my co-teachers this year has been watching them evolve into educators who have become sensitized to and skillful in structuring their classrooms to better support their English learners. More and more often I look around my co-taught classroom at my colleague as she’s presenting the whole-class lesson, smile, and think, “My work here is done. I don’t think she even needs me…” For an EL educator, it’s the best feeling…ever!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up HERE to receive freebies, announcements, and just to get to know us! Looking for new ideas and graduate credits? Visit our Online Professional Development School! Please visit the ELP website to meet the team and learn more about our services.

No doubt, many of you currently have students in your classrooms who have difficult names to pronounce or different spellings of popular names. The challenge when working with many ELL students is being able to connect with the students on an individual level despite the language barrier. Learning their names and being able to pronounce them correctly is very important for ELL students—especially for new, incoming students. Names are representations of who we are and where we come from. For many students, the significance, spelling, and pronunciation of their name means more to them now that they are in a new, unfamiliar environment. This is not to say that many students won’t change their name, because many will. They may modify their name to include nicknames or even slightly change the spelling of their name, and that is okay because it is their choice. So, for now, embrace those difficult-to-pronounce names and practice rolling your Rs because I promise that, as the teacher,

No doubt, many of you currently have students in your classrooms who have difficult names to pronounce or different spellings of popular names. The challenge when working with many ELL students is being able to connect with the students on an individual level despite the language barrier. Learning their names and being able to pronounce them correctly is very important for ELL students—especially for new, incoming students. Names are representations of who we are and where we come from. For many students, the significance, spelling, and pronunciation of their name means more to them now that they are in a new, unfamiliar environment. This is not to say that many students won’t change their name, because many will. They may modify their name to include nicknames or even slightly change the spelling of their name, and that is okay because it is their choice. So, for now, embrace those difficult-to-pronounce names and practice rolling your Rs because I promise that, as the teacher,  counselor, or school administrator, you being able to correctly say your student’s name means more to them than you will ever know. It is recognizing and accepting them for who they are and what they represent. Names make up who we are; they are part of our identity, and our identity is unshakably tethered to our self-esteem. Promoting positive environments where students feel accepted and connected can help promote school success for the English language learner.

counselor, or school administrator, you being able to correctly say your student’s name means more to them than you will ever know. It is recognizing and accepting them for who they are and what they represent. Names make up who we are; they are part of our identity, and our identity is unshakably tethered to our self-esteem. Promoting positive environments where students feel accepted and connected can help promote school success for the English language learner. Included below is a great activity that promotes name association with positive personality characteristic traits. Students can work on beginning to identify positive aspects about themselves and work on being able to share them out loud with each other in a classroom setting.

Included below is a great activity that promotes name association with positive personality characteristic traits. Students can work on beginning to identify positive aspects about themselves and work on being able to share them out loud with each other in a classroom setting. I’d love for you to share how this activity worked for your students and/or how you modified the activity to make it even better. Drop us a note at

I’d love for you to share how this activity worked for your students and/or how you modified the activity to make it even better. Drop us a note at  Graciela Williams “Gracie” is a licensed bilingual school social worker in Annapolis, Maryland. Gracie currently works with newcomer students and runs several social skills groups around the county. She specializes in working with international students who have experienced trauma. She has done extensive work incorporating and facilitating student and parent reunification groups within the school system. Gracie has worked as an Adult ESL teacher and program manager for literacy centers in South Carolina and Colorado. She has a bachelor’s degree in counseling from Bob Jones University and a master’s degree in social work from the University of New England. Gracie is also an Adjunct Professor for Goucher College, where she teaches a graduate level seminar course regarding At Risk Students, and she is an Adjunct Community Faculty for The University of New England providing field instruction to current MSW students.

Graciela Williams “Gracie” is a licensed bilingual school social worker in Annapolis, Maryland. Gracie currently works with newcomer students and runs several social skills groups around the county. She specializes in working with international students who have experienced trauma. She has done extensive work incorporating and facilitating student and parent reunification groups within the school system. Gracie has worked as an Adult ESL teacher and program manager for literacy centers in South Carolina and Colorado. She has a bachelor’s degree in counseling from Bob Jones University and a master’s degree in social work from the University of New England. Gracie is also an Adjunct Professor for Goucher College, where she teaches a graduate level seminar course regarding At Risk Students, and she is an Adjunct Community Faculty for The University of New England providing field instruction to current MSW students.