Becky Guzman is a full-time ESL teacher in Maryland. She is also a professional development creator and facilitator with English Learner Portal.

Becky Guzman is a full-time ESL teacher in Maryland. She is also a professional development creator and facilitator with English Learner Portal.

“So, what is the big deal with these thinking verbs?!” asked the newest ESL teacher on my team. I was getting ready to sit down and explain to her the importance of academic vocabulary, tier II vocabulary, how great the thinking verb icons were in providing a symbol to represent each verb, etc. I then realized that before I started to coach her on what this great tool was, I may need to also provide her with some specific ideas for how to use this wonderful instructional tool.

My colleague was referring to the new thinking verb icons I was using in my lessons. While I’ve used various icon ideas in the past, this new tool  was recently shared by English Learner Portal in the format of a “Thinking Verb Bilingual Placemat”. (You can download a copy for free HERE.)

was recently shared by English Learner Portal in the format of a “Thinking Verb Bilingual Placemat”. (You can download a copy for free HERE.)

My colleague was called to a meeting, so we tabled the conversation about the thinking verbs until later that afternoon. This was great, now I would have some time to think about the many ways in which I use them, and how I have observed other ESL teachers and classroom teachers using them so that I would sound like a much more knowledgeable and wise coach during our afternoon chat.

As I sat at my desk thinking about this, I could easily verbalize the reasons why she should use the thinking verb icons, as I had lots of training on the importance of academic language and the difference between social and academic language. I had taken book studies on teaching content vocabulary and knew that students’ proficiency with academic language is critical for reading comprehension and overall academic success.

As I sat at my desk thinking about this, I could easily verbalize the reasons why she should use the thinking verb icons, as I had lots of training on the importance of academic language and the difference between social and academic language. I had taken book studies on teaching content vocabulary and knew that students’ proficiency with academic language is critical for reading comprehension and overall academic success.

I thought about ways in which I used the thinking verbs and found myself limited to 1-2 “go to” ideas. I had gotten so used to using these specific ways that I had trouble quickly recalling other ways. Challenging myself, I took the time to brainstorm some ideas for my colleague and for you!

Activities and strategies for using the Thinking Verb icons:

-

Content and Language Outcomes-Replacing the verb in your outcome with the thinking verb icon allows students to have a visual representation of what that verb means. Students will visualize the actions they will take with the objective.

Content and Language Outcomes-Replacing the verb in your outcome with the thinking verb icon allows students to have a visual representation of what that verb means. Students will visualize the actions they will take with the objective. - Making Outcomes “Messy”- This strategy is great for explicitly going over outcomes at the beginning of the lesson in order for students to understand exactly what they will be learning. I like to use the icons in place of the verbs (words) and ask students to tell me what they think the verb means. I usually write their ideas or draw pictures (primary grades) directly around the icon on the actual outcome. Once students have had a chance to discuss what they think it means, I read them the correct definition or tell them what it means. We may also come up with some other examples of when that verb is used.

- “Mirrors Up” Outcomes Strategy– When introducing your outcomes to students, it is always better to make it a kinesthetic activity. A great way to use the thinking verbs is to place the icons on your outcomes. You ask students to put their “mirrors up” and they hold their hands up. They copy you, repeating after you as you read the outcome. When you get to the thinking verb, have students help you come up with motions to match that verb. You will be surprised how much students love coming up with motions for each and how much more they will remember the words!

- Vocabulary Games: “Taboo”– Students love this game in which one student faces away from the displayed thinking verb icon. The rest of the students must give him/her clues to describe that verb without telling them the word. The student must guess the actual thinking verb. It’s a great way to review the meaning of a number of thinking verbs!

- Thinking Verb Bookmarks- The bookmarks help students see the thinking verbs in action! I create bookmarks with all of the thinking verb icons and labels only, no definitions. The bookmark is laminated. As students read and they come upon one of the thinking verbs in the text, they make a tally mark on their bookmark. Higher proficiency students can note how the word was used in the text.

- Lesson/Activity Closure– I like to show students a few thinking verb icons or have them use the bookmark at the conclusion of a lesson or activity. I ask students to reflect and evaluate which verb they think we used during the lesson and why they think that. This is also a great way to formatively assess if students know the meaning of the words.

- Activity: Thinking Verb Forms–

When there is time, and especially if it is a newly introduced verb, I like to ask students to help me come up with a list of the other forms of the verb and we will list them near the icon on the actual outcome. (example: Identify-Identified, identifying).

When there is time, and especially if it is a newly introduced verb, I like to ask students to help me come up with a list of the other forms of the verb and we will list them near the icon on the actual outcome. (example: Identify-Identified, identifying). - Bilingual Thinking Verbs– For my students who are already pretty literate in Spanish, I like to introduce them to the verb in English and see if they can come up with the Spanish word before I show it to them. We then brainstorm some ways in which that verb is used in Spanish and discuss any cognates.

- Thinking Verbs Memory Game– I have played this with students and it is a great vocabulary review. Students take turns flipping over cards and must find matches between the thinking verb icon/word and the definitions. Another variation of this game is to match the English and Spanish icons. They must read the words correctly in English and Spanish when they find the match. You could also have students give the definition when they find the match depending on the students’ language proficiency.

- Planning Differentiated Learning Outcomes– I have used the icons when planning my lesson outcomes. I know my students’ language proficiency and can

see how some of the verbs may build on others. I especially use them when planning for my small group lessons. For example, in my three math groups, one group has an average language proficiency of 1.0-2.0 whereas the next group has a proficiency of 3.0 and the third group an average language proficiency of 4.0. My outcomes are related to being able to read decimal numbers to the thousandths. Because of language demand, I created different outcomes. My P:1.0-2.0 language group was focused on identifying the decimal numbers. My P:3.0 group had to read and compare the decimal numbers, and my P:4.0 group had to read and compare and contrast the decimal numbers. I knew that students would not be able to compare and/or contrast until they were able to first identify and so the thinking verbs helped me to plan my learning outcomes based on my students’ different language and content needs. Remember, I was focused on language while my content co-teacher was focused on the grade level math outcomes for all students.

see how some of the verbs may build on others. I especially use them when planning for my small group lessons. For example, in my three math groups, one group has an average language proficiency of 1.0-2.0 whereas the next group has a proficiency of 3.0 and the third group an average language proficiency of 4.0. My outcomes are related to being able to read decimal numbers to the thousandths. Because of language demand, I created different outcomes. My P:1.0-2.0 language group was focused on identifying the decimal numbers. My P:3.0 group had to read and compare the decimal numbers, and my P:4.0 group had to read and compare and contrast the decimal numbers. I knew that students would not be able to compare and/or contrast until they were able to first identify and so the thinking verbs helped me to plan my learning outcomes based on my students’ different language and content needs. Remember, I was focused on language while my content co-teacher was focused on the grade level math outcomes for all students.

Any list I come up with certainly won’t include all the potential ways that thinking verbs could be used to support instruction. I was happy that I at least had a few ideas and suggestions for my new coworker to get her started. I know that there are tons of vocabulary strategies and activities out there that would also be great for teaching our English learners (and ALL students) these thinking verbs and other tier II vocabulary which is so critical to accessing grade level standards. The most important thing is that the more we expose our English learners and involve them in playing with and using this academic language, the more successful they can be academically. It is not enough for them to be able to socially communicate in the English language, they must be explicitly taught academic language and critical thinking skills such as the thinking verbs.

Any list I come up with certainly won’t include all the potential ways that thinking verbs could be used to support instruction. I was happy that I at least had a few ideas and suggestions for my new coworker to get her started. I know that there are tons of vocabulary strategies and activities out there that would also be great for teaching our English learners (and ALL students) these thinking verbs and other tier II vocabulary which is so critical to accessing grade level standards. The most important thing is that the more we expose our English learners and involve them in playing with and using this academic language, the more successful they can be academically. It is not enough for them to be able to socially communicate in the English language, they must be explicitly taught academic language and critical thinking skills such as the thinking verbs.

How are you using the Thinking Verbs Bilingual Placemat or icons with your students? We’d love to have you share ideas with us and perhaps even write a blog post! Send your thoughts to info@englishlearnerportal.com and you could win a set of Thinking Verb Icon Magnets for your classroom. Haven’t downloaded your Thinking Verb Bilingual Placemat yet? You can find it HERE!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up HERE to receive freebies, announcements, and just to get to know us! Looking for new ideas and graduate credits? Visit our Online Professional Development School! Please visit the ELP website to meet the team and learn more about our services.

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up HERE to receive freebies, announcements, and just to get to know us! Looking for new ideas and graduate credits? Visit our Online Professional Development School! Please visit the ELP website to meet the team and learn more about our services.

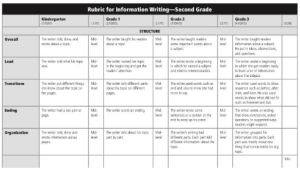

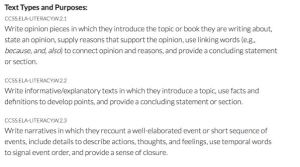

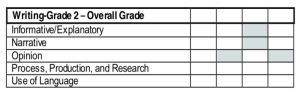

and with it, the first report card. As an ESL teacher in my district, my grading and reporting obligation has usually been met by submitting WIDA proficiency scores for the four skill areas on content we have studied and assessed throughout the marking period. USUALLY, that is, until this year when I became a co-teacher and BFF with the Lucy Calkins writing program.

and with it, the first report card. As an ESL teacher in my district, my grading and reporting obligation has usually been met by submitting WIDA proficiency scores for the four skill areas on content we have studied and assessed throughout the marking period. USUALLY, that is, until this year when I became a co-teacher and BFF with the Lucy Calkins writing program. For the first time in many years I feel like a content teacher, and I want my students to feel evaluated – by me – not only on their English language proficiency, but also on their growing proficiency as writers. Ah, but

For the first time in many years I feel like a content teacher, and I want my students to feel evaluated – by me – not only on their English language proficiency, but also on their growing proficiency as writers. Ah, but  for measuring content mastery in writing. These give teachers the benchmarks for measuring mastery of student progress in grade-level writing ability.

for measuring content mastery in writing. These give teachers the benchmarks for measuring mastery of student progress in grade-level writing ability. punctuation, and sentence mechanics. This presumably lets parents and their children know if they are making acceptable progress in their studies.

punctuation, and sentence mechanics. This presumably lets parents and their children know if they are making acceptable progress in their studies. disclosure, I truly did not even consider the implications of grading until it was already too late for this marking period. I had assumed that, per usual, I could rely on my WIDA proficiency levels to “grade” my English learners, and on my mainstream teachers for classroom grades in writing.

disclosure, I truly did not even consider the implications of grading until it was already too late for this marking period. I had assumed that, per usual, I could rely on my WIDA proficiency levels to “grade” my English learners, and on my mainstream teachers for classroom grades in writing. conferences. Therefore, as I sat through one conference after another hearing some of my favorite teachers offer vague and somewhat superficial explanations for how our students were progressing and being graded in writing, I realized, “We have TOTALLY failed these students.” Not only have we not given them clear and quantitative criteria for measuring their progress towards mastering the content area, we have not formulated a clear and purposeful plan for building on what they already know and are able to do now in order to improve their writing in the future.

conferences. Therefore, as I sat through one conference after another hearing some of my favorite teachers offer vague and somewhat superficial explanations for how our students were progressing and being graded in writing, I realized, “We have TOTALLY failed these students.” Not only have we not given them clear and quantitative criteria for measuring their progress towards mastering the content area, we have not formulated a clear and purposeful plan for building on what they already know and are able to do now in order to improve their writing in the future. and criteria for success that will not only inform students of our shared expectations for writing but which also will serve to better inform the rationale behind their report card grades.

and criteria for success that will not only inform students of our shared expectations for writing but which also will serve to better inform the rationale behind their report card grades.

However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.

However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.  can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

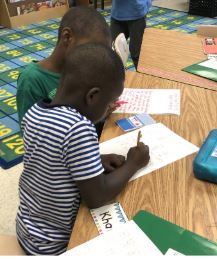

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child.

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child. how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994)

how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994) Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

But as I reminded myself and my team last week, in a diverse school like ours (70% FARMS, 40% Hispanic, 40% AA, 55% ELL)

But as I reminded myself and my team last week, in a diverse school like ours (70% FARMS, 40% Hispanic, 40% AA, 55% ELL)  understand the disconnect.

understand the disconnect.  Like most ESL educators, I’ve attended training, read the word of experts – even talked to them, taken online courses, and attended my district’s workshops. But nothing – NOTHING – helps teachers more than the experiences of other teachers. I’m all alone in my school as I struggle to work this out; I hope you will share what you’ve tried, what worked, and other strategies and ideas you have tried. “Alone we can do so little. Together we can do so much.” My students need you, and there is

Like most ESL educators, I’ve attended training, read the word of experts – even talked to them, taken online courses, and attended my district’s workshops. But nothing – NOTHING – helps teachers more than the experiences of other teachers. I’m all alone in my school as I struggle to work this out; I hope you will share what you’ve tried, what worked, and other strategies and ideas you have tried. “Alone we can do so little. Together we can do so much.” My students need you, and there is

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?”

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?” composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?”

composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?” rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”

rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”  I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel!

I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel! If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

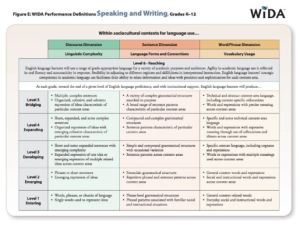

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2.

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2. How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at.

How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at. Personal issues

Personal issues English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.

English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.

these events, students and/or their families typically set up tables to highlight their countries and cultures and the rest of the students and families walk from table to table sampling food and looking at artifacts and maps. While organizers of these events have good intentions and aim to honor their students’ cultural backgrounds, sometimes these events can seem

these events, students and/or their families typically set up tables to highlight their countries and cultures and the rest of the students and families walk from table to table sampling food and looking at artifacts and maps. While organizers of these events have good intentions and aim to honor their students’ cultural backgrounds, sometimes these events can seem  tokenistic. How can we build family comfort in schools throughout the school year? With 79% of teachers in the U.S. being white* and 25% of students being children of immigrants, getting to know the cultural backgrounds of students requires a deeper dive.

tokenistic. How can we build family comfort in schools throughout the school year? With 79% of teachers in the U.S. being white* and 25% of students being children of immigrants, getting to know the cultural backgrounds of students requires a deeper dive. There are often two goals of international nights. The first is for students to learn more about other cultures and the second is for teachers to learn more about the backgrounds of their students and their families. With those goals in mind, what are 10 possible alternatives to international night?

There are often two goals of international nights. The first is for students to learn more about other cultures and the second is for teachers to learn more about the backgrounds of their students and their families. With those goals in mind, what are 10 possible alternatives to international night?