by Mia Ariela Allen

Mia is founder and Director of Professional Learning for Denver-based 4Ed Consulting. Mia currently is working with school districts nationally and internationally to develop language-rich learning environments. Mia is also a professional development facilitator and content developer for English Learner Portal.

As English Learner Portal prepares to celebrate Multicultural Children’s Book Day  on January 25th, Mia shares her thoughts on supporting our students with literature. Hear the other English Learner Portal team members share their favorite multicultural children’s books by visiting https://englishlearnerportal.teachable.com.

on January 25th, Mia shares her thoughts on supporting our students with literature. Hear the other English Learner Portal team members share their favorite multicultural children’s books by visiting https://englishlearnerportal.teachable.com.

Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world, Freire & Macedo (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world.

Even if your students have not been exposed to all of the recent news stories about or even photos of refugees, they may have heard about the crisis impacting young children and families around the world. Many of our nation’s refugee families, are resettling in communities across the United States.

When we are talking to our students about the global refugee crisis, it is very important to reinforce your own student’s safety. The journey that many of our newcomers have had to take was incredibly dangerous. As you consider the students in your class, you will want to first consider these journeys and how to relate the stories about refugees to their experiences. As our students are able to begin to relate to these journeys to their own sense of safety, it will be important to first help students create their understanding of who a refugee is, where refugees may come from, and what newly arrived refugees might need to feel safe and welcomed in their new communities.

Children’s literature is an excellent way to support difficult discussions and to foster empathy and understanding about the refugee crisis. These children’s books focus on two central and common themes; the refugee journey to safety and their experiences within the new community.

I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien

I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien

K-1st Grade Selection

This simple story is told through the eyes of three newcomer children; Jin from Korea, Fatima from Somalia, and Maria from Guatemala. All three children share the struggles of feeling safe, welcome and comfortable in their new American schools. Each student shares the challenge of communicating in English both in the classroom and on the playground. This simple and approachable story helps facilitate wonderful classroom discussion on community, collaboration, and caring for one another.

The Colour of Home by Mary Hoffman & Karin Littlewood

The Colour of Home by Mary Hoffman & Karin Littlewood

1st-2nd Grade Selection

Hassan, a 1st grade student from Somalia talks about feeling homesick in his new community. Hassan and his family have just recently arrived in the United States after fleeing war and spending time waiting in a refugee camp. Like many newly resettled refugees, Hassan misses speaking Somali, his home, his community and is struggling to communicate in his new language, English. Hassan is especially missing his cat, Musa, who he had to leave behind. When Hassan arrives in his new home, he believes he has left all of the colours of his world behind. This incredibly vivid story helps our students feel empathy and gain a better understanding of some of the experiences a student their age may have overcome to begin a new life in a new community.

Stepping Stones- A Refugee Family’s Journey

Stepping Stones- A Refugee Family’s Journey

3rd Grade and Beyond Selection

Our final selection is a beautiful story told by Margaret Ruurs and accompanied by the art of Nizar Ali Badr. As Ruurs highlights in the forward, the rock painting illustrations were created by Nazir, an artist in Syria. The l rock illustrations highlight the story, in both English and Arabic, a journey to safety. Much like the other stories, the newly resettled family is both hopeful and thankful for their new home and community.

Additional selections to consider for your classroom library

- Ada, A.(2002), I Love Saturdays and Domingos

- (1998). Mariante’s Story: Painted Words & Spoken Memories.

- Anzalüda, G. (1993).Friends from the Other Side

- Applegate, K. Home of the Brave.

- Beckwith, K. Playing War.

- Bunting, E. (1993) Going Home

- Burg, A. Serafina’s Promise.

- Cha, D. Dia’s Story Cloth: The Hmong People’s Journey to Freedom

- Choi, Y. (2001). The Name Jar

- Cohen, S. Mai Ya’ Long Journey.

- Danticat, E. Mama’s Nightingale: A story of immigration and separation.

- Deitz-Shea, P. The Whispering Cloth

- Del Rizzo, S. My Beautiful Birds

- DePrince, M. Taking Flight: From War Orphanto Star Ballerina.

- Duncan, D.

- Flores-Galbis, E. 90 Miles to Havana

- Garza, C.L. (1996). In My Family: En mi familia.

- Gillick, M. Once they had a country: Two Teenage Refugees in the Second World War

- Gutiérrez, R. K’naan.

- Hampton, M. The Cat of Kosovo

- Hoffman, M. The Color of Home

- Jimenez, F. (2001). Breaking Through

- Jimenez, F. (1997a) The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child

- Kuntz, D. Lost and Found Cat: The True Story of Kunkush’s Incredible Journey

- Lai, T. Inside Out and Back Again.

- Laure Bondoux, A. A Time of Miracles

- Lofthouse, L. Ziba Came on a Boat.

- Lord, M. A Song for Cambodia

- Martinez, V. (1996) Parrot in the Oven: Mi Vida.

- Mead, A Girls of Kosovo

- McCarney, R. Where will I live.

- Mikaelsen, B. Red Midnight.

- Palacios, A. (1997). One City, One School, Many Foods.

- Park, F. My Freedom Trip.

- Paulsen, (1995). La tortelleria

- Pinkey, A. The Red Pencil.

- Ruurs, M. Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey (Arabic & English Edition)

- Sanna, F. The Journey.

- Simon, R. Oskar and the Eight Blessings.

- Smith Milway, K. The Banana-Leaf Ball: How Play Can Change the World

- Soto, G. (1997). Buried Onions

- John, W. Outcasts United: The Story of a Refugee Soccer Team That Changed a Town

- Tsang, N. (2003) Rice All Day

- Young, R.

- Wild, M. The Treasure Box.

- Wilkes, S. Out of Iraq: Refugees’ Stories in Words, Paintings and Music.

- Williams, M. Brothers in Hope: The Story of the Lost Boys of Sudan

- Williams, K. Four Feet, Two Sandals.

- Woodruff, E. The Memory Coat.

Do you have a favorite multicultural children’s book you’d like to share in our online collection? Make a video of you sharing your favorite and reasons why and send it to info@englishlearnerportal.com. We’d love to have you!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up HERE to receive freebies, announcements, and just to get to know us! Looking for new ideas and graduate credits? Visit our Online Professional Development School! Please visit the ELP website to meet the team and learn more about our services.

by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom.

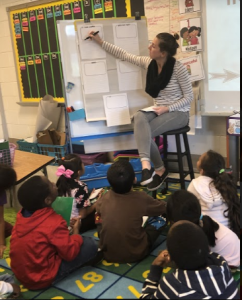

by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom. return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.”

return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.” so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.

so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.  probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

Susan is an elementary ESL teacher in Montgomery County Public Schools and consultant with English Learner Portal.

Susan is an elementary ESL teacher in Montgomery County Public Schools and consultant with English Learner Portal.  However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.

However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.  can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child.

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child. how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994)

how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994) Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?”

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?” composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?”

composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?” rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”

rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”  I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel!

I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel! If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

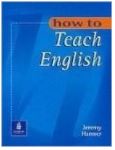

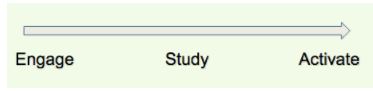

The ESA model—which involves equally teacher and learners—is based on the ideas of Jeremy Harmer from his influential book,

The ESA model—which involves equally teacher and learners—is based on the ideas of Jeremy Harmer from his influential book,

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2.

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2. How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at.

How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at. Personal issues

Personal issues English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.

English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.

cafeteria had a different type of table one month out of the year. From second grade on up, I began to practice fasting during the month of Ramadan. To fast during the month of Ramadan means to not have any food or drink from sunup to sundown. At this young of an age, I didn’t practice it to its full extent. Sometimes I fasted half days, other times I completed whole days. The “fasting table” that I shared with my Muslim peers was placed smack dab in the middle of the cafeteria, so the cafeteria ladies could keep an eye on those “fasting Arab kids”. Yes.. I said it.. the fasting kids (who were not eating lunch) sat in the

cafeteria had a different type of table one month out of the year. From second grade on up, I began to practice fasting during the month of Ramadan. To fast during the month of Ramadan means to not have any food or drink from sunup to sundown. At this young of an age, I didn’t practice it to its full extent. Sometimes I fasted half days, other times I completed whole days. The “fasting table” that I shared with my Muslim peers was placed smack dab in the middle of the cafeteria, so the cafeteria ladies could keep an eye on those “fasting Arab kids”. Yes.. I said it.. the fasting kids (who were not eating lunch) sat in the  When answering these questions, it is important to think about the science behind them. “The brain’s two prime directives are to stay safe and be happy.” (Hammond 2015) With that said, learning is difficult when a child is preoccupied about their safety. Yes, physically safety is key. But emotionally safety, can also really impact a child’s learning. I attended a school where teachers really did their best to make me feel secure about who I was. With this, I was able to focus on learning because I didn’t feel that my identity put me in jeopardy.

When answering these questions, it is important to think about the science behind them. “The brain’s two prime directives are to stay safe and be happy.” (Hammond 2015) With that said, learning is difficult when a child is preoccupied about their safety. Yes, physically safety is key. But emotionally safety, can also really impact a child’s learning. I attended a school where teachers really did their best to make me feel secure about who I was. With this, I was able to focus on learning because I didn’t feel that my identity put me in jeopardy. students really express themselves. Lots of teachers are trying something new by having students create “vision boards”. Vision boards not only teach teachers about a student’s background, they also teach teachers about students’ goals. Students can use the vision board later to refer to their own goals. A vision board can take form in any way. It just has to be goal oriented.

students really express themselves. Lots of teachers are trying something new by having students create “vision boards”. Vision boards not only teach teachers about a student’s background, they also teach teachers about students’ goals. Students can use the vision board later to refer to their own goals. A vision board can take form in any way. It just has to be goal oriented.  When these experiences are being provided in the classroom, it gives the child a pleasant memory of their school experience. Valuing that child goes a long way for a lifetime of confidence in who they are. Going back to brain science, the schema that is built for a child of experiences in the classroom will help reduce anxiety towards future classroom experiences. It will also help the child overcome adversity when they experience it because a teacher helped build a foundation of confidence.

When these experiences are being provided in the classroom, it gives the child a pleasant memory of their school experience. Valuing that child goes a long way for a lifetime of confidence in who they are. Going back to brain science, the schema that is built for a child of experiences in the classroom will help reduce anxiety towards future classroom experiences. It will also help the child overcome adversity when they experience it because a teacher helped build a foundation of confidence. community. My conversations with my students taught me so much about traditions. I continued to engage in them. Years later, I ended up working in a Middle School fifteen minutes away in Albany Park that served a large Hispanic community. The school had a significant Puerto Rican population. My conversations a decade prior to that with students helped me build relationships in my new environment as a language arts teacher then later as a Dean of Instruction. Students felt safe with me because I tried to learn their culture and bring it into the school and classroom.

community. My conversations with my students taught me so much about traditions. I continued to engage in them. Years later, I ended up working in a Middle School fifteen minutes away in Albany Park that served a large Hispanic community. The school had a significant Puerto Rican population. My conversations a decade prior to that with students helped me build relationships in my new environment as a language arts teacher then later as a Dean of Instruction. Students felt safe with me because I tried to learn their culture and bring it into the school and classroom.

Within a week of our arrival, Muzyen and her family greeted us and welcomed us. When I came home from errands, they eagerly kept the kids while I shuttled groceries up the three flights of stairs. Muzyen understood my younger daughter’s nervous cries and stood singing to her in the hallway as they watched me work. When her daughters were home, one of the daughters would keep my girls entertained while I cleaned the house or cooked dinner – teaching them songs, hand-games, and stories. When my family returned from outings and clomped and chattered our way up the stairs, Muzyen’s family would open the door to talk with us and visit with our little kids. Occasionally, on long afternoons, Muzyen would break up the monotony of my day by inviting me for tea. She offered sweet pastries and savory dishes as we fumbled through small-talk and conversation.

Within a week of our arrival, Muzyen and her family greeted us and welcomed us. When I came home from errands, they eagerly kept the kids while I shuttled groceries up the three flights of stairs. Muzyen understood my younger daughter’s nervous cries and stood singing to her in the hallway as they watched me work. When her daughters were home, one of the daughters would keep my girls entertained while I cleaned the house or cooked dinner – teaching them songs, hand-games, and stories. When my family returned from outings and clomped and chattered our way up the stairs, Muzyen’s family would open the door to talk with us and visit with our little kids. Occasionally, on long afternoons, Muzyen would break up the monotony of my day by inviting me for tea. She offered sweet pastries and savory dishes as we fumbled through small-talk and conversation. everyone prepared for a big event. The neighbors would clean their homes top to bottom – so thoroughly that they would even hang their carpets over the balconies to dry after hand-washing them. The community scoured the local markets and stores for specialty foods they would use for traditional meals, toys to give their children, and outfits to wear for the festivities. Furthermore, people stocked up their kitchens as shops would be closed for a few days.

everyone prepared for a big event. The neighbors would clean their homes top to bottom – so thoroughly that they would even hang their carpets over the balconies to dry after hand-washing them. The community scoured the local markets and stores for specialty foods they would use for traditional meals, toys to give their children, and outfits to wear for the festivities. Furthermore, people stocked up their kitchens as shops would be closed for a few days. Muzyen knew what it was to be an outsider. Because of that, she invited us to join her family’s festivities. One of the more intimate components of their celebrations was a breakfast to break their fast. Muzyen had already graciously included our family at a few of their iftar dinner meals. The breakfast marked the beginning of a three-day celebration. This was more of a family affair. Normally new friends or neighbors might visit on the third day, but in my observation not typically the first breakfast.

Muzyen knew what it was to be an outsider. Because of that, she invited us to join her family’s festivities. One of the more intimate components of their celebrations was a breakfast to break their fast. Muzyen had already graciously included our family at a few of their iftar dinner meals. The breakfast marked the beginning of a three-day celebration. This was more of a family affair. Normally new friends or neighbors might visit on the third day, but in my observation not typically the first breakfast. Laurie Meberg has been working cross-culturally for seventeen years as a teacher, community developer, and refugee liaison. She learned two languages through immersion and tried to learn a third through friendships in a multicultural community. She has frequently helped emerging English speakers by being a conversation partner – mostly over cups of tea. She lives in Colorado with her husband and three children.

Laurie Meberg has been working cross-culturally for seventeen years as a teacher, community developer, and refugee liaison. She learned two languages through immersion and tried to learn a third through friendships in a multicultural community. She has frequently helped emerging English speakers by being a conversation partner – mostly over cups of tea. She lives in Colorado with her husband and three children.

No doubt, many of you currently have students in your classrooms who have difficult names to pronounce or different spellings of popular names. The challenge when working with many ELL students is being able to connect with the students on an individual level despite the language barrier. Learning their names and being able to pronounce them correctly is very important for ELL students—especially for new, incoming students. Names are representations of who we are and where we come from. For many students, the significance, spelling, and pronunciation of their name means more to them now that they are in a new, unfamiliar environment. This is not to say that many students won’t change their name, because many will. They may modify their name to include nicknames or even slightly change the spelling of their name, and that is okay because it is their choice. So, for now, embrace those difficult-to-pronounce names and practice rolling your Rs because I promise that, as the teacher,

No doubt, many of you currently have students in your classrooms who have difficult names to pronounce or different spellings of popular names. The challenge when working with many ELL students is being able to connect with the students on an individual level despite the language barrier. Learning their names and being able to pronounce them correctly is very important for ELL students—especially for new, incoming students. Names are representations of who we are and where we come from. For many students, the significance, spelling, and pronunciation of their name means more to them now that they are in a new, unfamiliar environment. This is not to say that many students won’t change their name, because many will. They may modify their name to include nicknames or even slightly change the spelling of their name, and that is okay because it is their choice. So, for now, embrace those difficult-to-pronounce names and practice rolling your Rs because I promise that, as the teacher,  counselor, or school administrator, you being able to correctly say your student’s name means more to them than you will ever know. It is recognizing and accepting them for who they are and what they represent. Names make up who we are; they are part of our identity, and our identity is unshakably tethered to our self-esteem. Promoting positive environments where students feel accepted and connected can help promote school success for the English language learner.

counselor, or school administrator, you being able to correctly say your student’s name means more to them than you will ever know. It is recognizing and accepting them for who they are and what they represent. Names make up who we are; they are part of our identity, and our identity is unshakably tethered to our self-esteem. Promoting positive environments where students feel accepted and connected can help promote school success for the English language learner. Included below is a great activity that promotes name association with positive personality characteristic traits. Students can work on beginning to identify positive aspects about themselves and work on being able to share them out loud with each other in a classroom setting.

Included below is a great activity that promotes name association with positive personality characteristic traits. Students can work on beginning to identify positive aspects about themselves and work on being able to share them out loud with each other in a classroom setting. I’d love for you to share how this activity worked for your students and/or how you modified the activity to make it even better. Drop us a note at

I’d love for you to share how this activity worked for your students and/or how you modified the activity to make it even better. Drop us a note at  Graciela Williams “Gracie” is a licensed bilingual school social worker in Annapolis, Maryland. Gracie currently works with newcomer students and runs several social skills groups around the county. She specializes in working with international students who have experienced trauma. She has done extensive work incorporating and facilitating student and parent reunification groups within the school system. Gracie has worked as an Adult ESL teacher and program manager for literacy centers in South Carolina and Colorado. She has a bachelor’s degree in counseling from Bob Jones University and a master’s degree in social work from the University of New England. Gracie is also an Adjunct Professor for Goucher College, where she teaches a graduate level seminar course regarding At Risk Students, and she is an Adjunct Community Faculty for The University of New England providing field instruction to current MSW students.

Graciela Williams “Gracie” is a licensed bilingual school social worker in Annapolis, Maryland. Gracie currently works with newcomer students and runs several social skills groups around the county. She specializes in working with international students who have experienced trauma. She has done extensive work incorporating and facilitating student and parent reunification groups within the school system. Gracie has worked as an Adult ESL teacher and program manager for literacy centers in South Carolina and Colorado. She has a bachelor’s degree in counseling from Bob Jones University and a master’s degree in social work from the University of New England. Gracie is also an Adjunct Professor for Goucher College, where she teaches a graduate level seminar course regarding At Risk Students, and she is an Adjunct Community Faculty for The University of New England providing field instruction to current MSW students.

these events, students and/or their families typically set up tables to highlight their countries and cultures and the rest of the students and families walk from table to table sampling food and looking at artifacts and maps. While organizers of these events have good intentions and aim to honor their students’ cultural backgrounds, sometimes these events can seem

these events, students and/or their families typically set up tables to highlight their countries and cultures and the rest of the students and families walk from table to table sampling food and looking at artifacts and maps. While organizers of these events have good intentions and aim to honor their students’ cultural backgrounds, sometimes these events can seem  tokenistic. How can we build family comfort in schools throughout the school year? With 79% of teachers in the U.S. being white* and 25% of students being children of immigrants, getting to know the cultural backgrounds of students requires a deeper dive.

tokenistic. How can we build family comfort in schools throughout the school year? With 79% of teachers in the U.S. being white* and 25% of students being children of immigrants, getting to know the cultural backgrounds of students requires a deeper dive. There are often two goals of international nights. The first is for students to learn more about other cultures and the second is for teachers to learn more about the backgrounds of their students and their families. With those goals in mind, what are 10 possible alternatives to international night?

There are often two goals of international nights. The first is for students to learn more about other cultures and the second is for teachers to learn more about the backgrounds of their students and their families. With those goals in mind, what are 10 possible alternatives to international night?