by Susan Zimmerman-Orozco

Susan is an elementary ESL teacher in Montgomery County Public Schools and consultant with English Learner Portal.

I love co-teaching with the Lucy Calkins program. I get to use my expertise as the purveyor of academic language. At the same time I’m learning from my co-teacher, my mainstream students, and the Lucy Calkins writing guide.

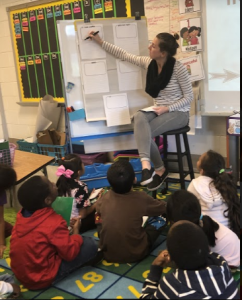

Once or twice a week I plan and teach a whole-class lessons that ESOL-izes concepts that I know are mystifying my English learners, or it anticipates confusion in upcoming lessons  by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom.

by providing background knowledge I know my students and other diverse learners will lack. As the self-appointed expert in academic language instruction, I’m always ready with daily language objectives, strategies, and activities to provide support that will extend my students’ language skills. I’m especially proud that, at the same time, I’m probably extending the academic language of 70% of the rest of my diverse classroom.

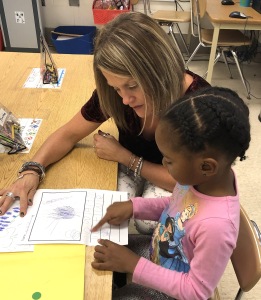

Arguably, however, the most valuable component of the Lucy Calkins approach to writing, and where I feel I make my most valuable contribution, comes from the frequent opportunities it provides for teacher-student conferencing. In the traditional Writing Process approach, dedicated teacher-student conferencing doesn’t appear until quite far along the continuum, after students have brainstormed, created drafts, peer edited, and revised their work. English learners, though, as we know, need quite a bit of hand-holding and scaffolding to be successful writers, especially if we want them to advance in their proficiency by adding more academic-level vocabulary and complexity to their writing.

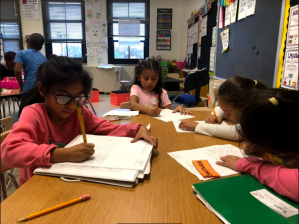

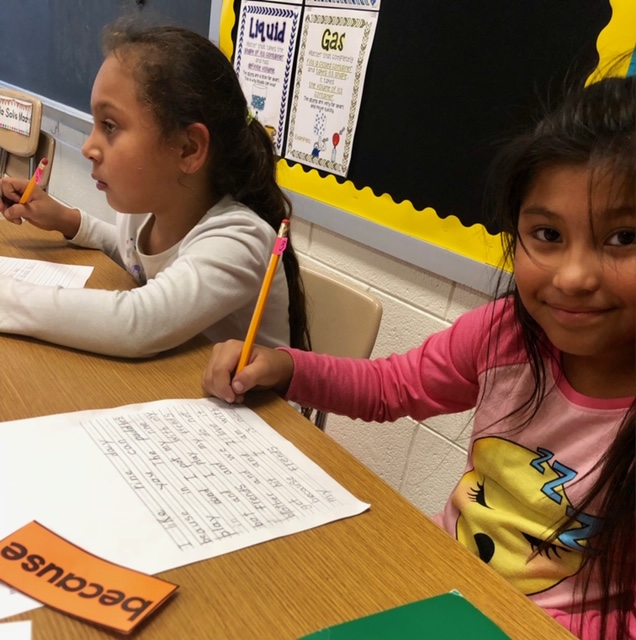

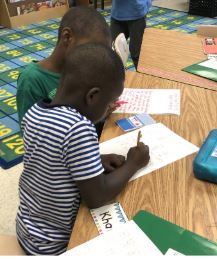

In our co-taught classrooms, daily, once a whole-class lesson is presented, students  return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.”

return to their places, usually with a writing partner, to work on their current writing. In our class, we maximize teacher-student conferencing time by grouping students at two large tables, each with a teacher. This configuration that allows us either to review student work in progress and make suggestions or to troubleshoot individual student needs as they arise, especially to answer their plaintive, “How do you spell…?” even though we invariably respond for the 100th time, “Sound it out, ” or “Look on the word wall.”

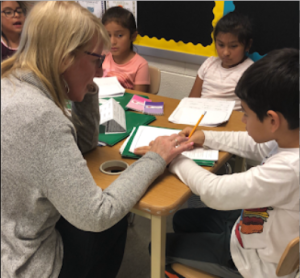

Our groups are fluid. Some students just prefer to work on their own, and we have some highly productive student partners who produce inspiring writing conferencing only with each other. I often work with non-English learners, and my amazing co-teacher, Tara, is  so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.

so beloved by some of my English learner girls that they usually make a bee-line to her group. The point is that there are two of us, and we are both committed to getting our kids the individualized help they need to succeed as writers.

Furthermore, and frankly, as a school with a highly diverse population, some of our students come to us better prepared than others to work independently. As Tara commented, “Conferencing in a group limits unwanted behaviors that would distract others. In a group setting, sitting all together at the table, I can conference with one student, get him or her on the right track, and quickly move on.”

She continued, “I feel all of our students need support, and more than anything they need reassurance that they’re doing the right thing.” Referring to some of our students with behavior concerns, she added, “Sometimes kids who are the most reluctant writers act out because they don’t want to fail. If I’m there with them, insisting they can do it, and helping them, I can show them that writing doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and they CAN succeed.”

I know I’m not alone in feeling that the Lucy Calkins Writing program in particular, and  probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

probably teaching writing in general, is challenging when English learners comprise a large portion of our class. I feel fortunate to be able to support my students, and my colleagues, by co-teaching writing. I can’t think of any other content area where my particular expertise in academic language has been more beneficial, not only to students, but also to my colleague.

One of the most satisfying and unexpected outcomes of working with my co-teachers this year has been watching them evolve into educators who have become sensitized to and skillful in structuring their classrooms to better support their English learners. More and more often I look around my co-taught classroom at my colleague as she’s presenting the whole-class lesson, smile, and think, “My work here is done. I don’t think she even needs me…” For an EL educator, it’s the best feeling…ever!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up HERE to receive freebies, announcements, and just to get to know us! Looking for new ideas and graduate credits? Visit our Online Professional Development School! Please visit the ELP website to meet the team and learn more about our services.

was recently shared by English Learner Portal in the format of a “Thinking Verb Bilingual Placemat”. (

was recently shared by English Learner Portal in the format of a “Thinking Verb Bilingual Placemat”. (

Content and Language Outcomes

Content and Language Outcomes When there is time, and especially if it is a newly introduced verb, I like to ask students to help me come up with a list of the other forms of the verb and we will list them near the icon on the actual outcome. (example: Identify-Identified, identifying).

When there is time, and especially if it is a newly introduced verb, I like to ask students to help me come up with a list of the other forms of the verb and we will list them near the icon on the actual outcome. (example: Identify-Identified, identifying). see how some of the verbs may build on others. I especially use them when planning for my small group lessons. For example, in my three math groups, one group has an average language proficiency of 1.0-2.0 whereas the next group has a proficiency of 3.0 and the third group an average language proficiency of 4.0. My outcomes are related to being able to read decimal numbers to the thousandths. Because of language demand, I created different outcomes. My P:1.0-2.0 language group was focused on identifying the decimal numbers. My P:3.0 group had to read and compare the decimal numbers, and my P:4.0 group had to read and compare and contrast the decimal numbers. I knew that students would not be able to compare and/or contrast until they were able to first identify and so the thinking verbs helped me to plan my learning outcomes based on my students’ different language and content needs. Remember, I was focused on language while my content co-teacher was focused on the grade level math outcomes for all students.

see how some of the verbs may build on others. I especially use them when planning for my small group lessons. For example, in my three math groups, one group has an average language proficiency of 1.0-2.0 whereas the next group has a proficiency of 3.0 and the third group an average language proficiency of 4.0. My outcomes are related to being able to read decimal numbers to the thousandths. Because of language demand, I created different outcomes. My P:1.0-2.0 language group was focused on identifying the decimal numbers. My P:3.0 group had to read and compare the decimal numbers, and my P:4.0 group had to read and compare and contrast the decimal numbers. I knew that students would not be able to compare and/or contrast until they were able to first identify and so the thinking verbs helped me to plan my learning outcomes based on my students’ different language and content needs. Remember, I was focused on language while my content co-teacher was focused on the grade level math outcomes for all students. Any list I come up with certainly won’t include all the potential ways that thinking verbs could be used to support instruction. I was happy that I at least had a few ideas and suggestions for my new coworker to get her started. I know that there are tons of vocabulary strategies and activities out there that would also be great for teaching our English learners (and ALL students) these thinking verbs and other tier II vocabulary which is so critical to accessing grade level standards. The most important thing is that the more we expose our English learners and involve them in playing with and using this academic language, the more successful they can be academically. It is not enough for them to be able to socially communicate in the English language, they must be explicitly taught academic language and critical thinking skills such as the thinking verbs.

Any list I come up with certainly won’t include all the potential ways that thinking verbs could be used to support instruction. I was happy that I at least had a few ideas and suggestions for my new coworker to get her started. I know that there are tons of vocabulary strategies and activities out there that would also be great for teaching our English learners (and ALL students) these thinking verbs and other tier II vocabulary which is so critical to accessing grade level standards. The most important thing is that the more we expose our English learners and involve them in playing with and using this academic language, the more successful they can be academically. It is not enough for them to be able to socially communicate in the English language, they must be explicitly taught academic language and critical thinking skills such as the thinking verbs. If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

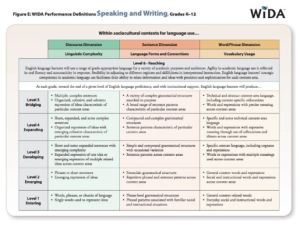

and with it, the first report card. As an ESL teacher in my district, my grading and reporting obligation has usually been met by submitting WIDA proficiency scores for the four skill areas on content we have studied and assessed throughout the marking period. USUALLY, that is, until this year when I became a co-teacher and BFF with the Lucy Calkins writing program.

and with it, the first report card. As an ESL teacher in my district, my grading and reporting obligation has usually been met by submitting WIDA proficiency scores for the four skill areas on content we have studied and assessed throughout the marking period. USUALLY, that is, until this year when I became a co-teacher and BFF with the Lucy Calkins writing program. For the first time in many years I feel like a content teacher, and I want my students to feel evaluated – by me – not only on their English language proficiency, but also on their growing proficiency as writers. Ah, but

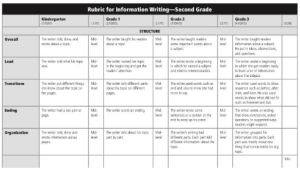

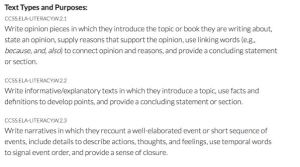

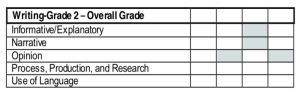

For the first time in many years I feel like a content teacher, and I want my students to feel evaluated – by me – not only on their English language proficiency, but also on their growing proficiency as writers. Ah, but  for measuring content mastery in writing. These give teachers the benchmarks for measuring mastery of student progress in grade-level writing ability.

for measuring content mastery in writing. These give teachers the benchmarks for measuring mastery of student progress in grade-level writing ability. punctuation, and sentence mechanics. This presumably lets parents and their children know if they are making acceptable progress in their studies.

punctuation, and sentence mechanics. This presumably lets parents and their children know if they are making acceptable progress in their studies. disclosure, I truly did not even consider the implications of grading until it was already too late for this marking period. I had assumed that, per usual, I could rely on my WIDA proficiency levels to “grade” my English learners, and on my mainstream teachers for classroom grades in writing.

disclosure, I truly did not even consider the implications of grading until it was already too late for this marking period. I had assumed that, per usual, I could rely on my WIDA proficiency levels to “grade” my English learners, and on my mainstream teachers for classroom grades in writing. conferences. Therefore, as I sat through one conference after another hearing some of my favorite teachers offer vague and somewhat superficial explanations for how our students were progressing and being graded in writing, I realized, “We have TOTALLY failed these students.” Not only have we not given them clear and quantitative criteria for measuring their progress towards mastering the content area, we have not formulated a clear and purposeful plan for building on what they already know and are able to do now in order to improve their writing in the future.

conferences. Therefore, as I sat through one conference after another hearing some of my favorite teachers offer vague and somewhat superficial explanations for how our students were progressing and being graded in writing, I realized, “We have TOTALLY failed these students.” Not only have we not given them clear and quantitative criteria for measuring their progress towards mastering the content area, we have not formulated a clear and purposeful plan for building on what they already know and are able to do now in order to improve their writing in the future. and criteria for success that will not only inform students of our shared expectations for writing but which also will serve to better inform the rationale behind their report card grades.

and criteria for success that will not only inform students of our shared expectations for writing but which also will serve to better inform the rationale behind their report card grades.

However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.

However, tasking 6 year-olds to come up with something they know and could teach someone about proved to be challenging for some students and their first efforts tended to be whatever topic their teacher had chosen for the lesson objective. Or, for reasons still not understood, octopuses.  can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

can be experts on. For example, even Mrs. Zimmerman’s grandson EJ, can be an expert!

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child.

We picked ourselves up, dusted ourselves off, and started all over again with a mini-review. And then…we LISTENED! We hunkered down with each of our students (something a lot easier to do in a co-teaching situation) and listened to what students were saying and what they thought they were writing. We pointed out confusions, prompted for opinions, gave thumbs up, and moved on to the next child. how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994)

how important student conferencing is. Those of us in highly diverse schools are so caught up in the minutia of scaffolding what good writing should look and sound like that we forget the point of it… “[We] are teaching the writer and not the writing. Our decisions must be guided by ‘what might help this writer’ rather than ‘what might help this writing’” (Lucy Calkins, 1994) Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

Student conferencing – working one on one with students – is too often a catch-as-catch-can occurrence, when in fact it is one of the most important tools in the LC writer’s toolbox. It needs to be carried out regularly in an an intentional and purposeful way. Good writers make connections with their readers – whether they are telling a story or writing an opinion. Good teachers make connections with their students. As you travel through the changing focus of your writing program throughout the school year, please don’t forget the reason we are teaching writing in the first place: to connect and build relationships with our most important audience, our students.

But as I reminded myself and my team last week, in a diverse school like ours (70% FARMS, 40% Hispanic, 40% AA, 55% ELL)

But as I reminded myself and my team last week, in a diverse school like ours (70% FARMS, 40% Hispanic, 40% AA, 55% ELL)  understand the disconnect.

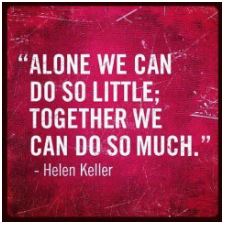

understand the disconnect.  Like most ESL educators, I’ve attended training, read the word of experts – even talked to them, taken online courses, and attended my district’s workshops. But nothing – NOTHING – helps teachers more than the experiences of other teachers. I’m all alone in my school as I struggle to work this out; I hope you will share what you’ve tried, what worked, and other strategies and ideas you have tried. “Alone we can do so little. Together we can do so much.” My students need you, and there is

Like most ESL educators, I’ve attended training, read the word of experts – even talked to them, taken online courses, and attended my district’s workshops. But nothing – NOTHING – helps teachers more than the experiences of other teachers. I’m all alone in my school as I struggle to work this out; I hope you will share what you’ve tried, what worked, and other strategies and ideas you have tried. “Alone we can do so little. Together we can do so much.” My students need you, and there is

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?”

I looked at her new story pages. “Can you read me the first page?” composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?”

composing is an integral step in the writing process. Nonetheless, I could tell that Jessica was getting annoyed with my constant insistence that she have a plan. Nevertheless, I was determined, ‘So, maybe the interesting part of your story is later? What happened in the end? Were you really happy? Did the cat do something funny?” rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”

rock back and forth on my tiny chair in despair. I looked deeply into her little 7-year old’s eyes, which clearly were not seeing what the big deal was all about, and pleaded with her, “Come on, Jessica, isn’t there ANYTHING interesting in your life you could write about?”  I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel!

I hope you will travel with us as we puzzle out the best way to use Lucy to help our ELLs – and all of our students. But even more importantly, I hope you will share your own challenges, your successes, and your suggestions and recommendations for using Lucy to show these, our most fragile, learners that not only can they succeed as writers but also excel! If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

If you aren’t already part of our mailing list, please sign up

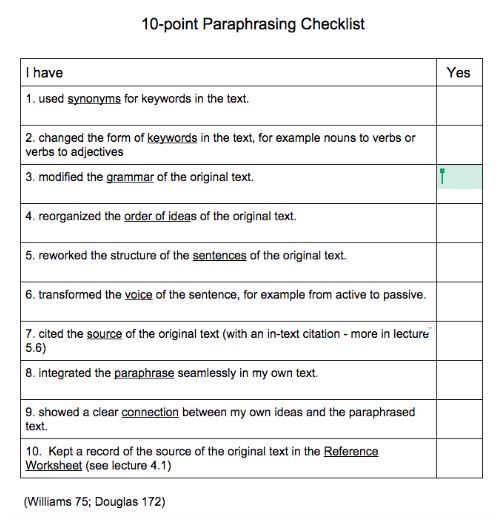

In this lecture, we tackle the serious problem of plagiarism. If a learner is caught plagiarizing, it can have serious consequences.

In this lecture, we tackle the serious problem of plagiarism. If a learner is caught plagiarizing, it can have serious consequences. the widespread use of the Internet (Successful 592).

the widespread use of the Internet (Successful 592). Learners need to get into the habit of reading carefully and taking good notes.

Learners need to get into the habit of reading carefully and taking good notes.

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2.

The first module explores the context for teaching and learning academic writing to adolescent English language learners. Topics include some effective ways for teaching academic writing, problems English language learners face in learning, the distinction between comprehensible input and output, and an overview of the WIDA writing rubrics with Kelly Reider. In today’s post, I want to share with you parts of Lecture 2. How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at.

How well do you know your students? Experienced teachers realize that they have to take the time to get to know their language students as human beings. I have always taken the time to relate to my students, to understand where they are coming from, to learn about their interests and hobbies, and to ask about what they are good at. Personal issues

Personal issues English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.

English language learners need to be taught how to write effectively. They need to know how to achieve their goals within a given context. Learners need to be taught how to express themselves effectively. They need to learn how to write well-organized, clear texts.